1. About this document

The five main sections are :

- general information about the practice

- the processes and activities of software development and management and their roles in the service value chain

- the organizations and people involved in software development and management

- the information and technology supporting software development and management

- considerations for partners and suppliers for software development and management.

1.1 ITIL® 4 QUALIFICATION SCHEME

Selected content from this document is examinable as a part of the following syllabuses:

- TIL Specialist: Create, Deliver and Support

- ITIL Specialist: High-velocity IT

Please refer to the respective syllabus documents for details.

2. General information

2.1 PURPOSE AND DESCRIPTION

The purpose of the software development and management practice is to ensure that applications meet internal and external stakeholder needs, in terms of functionality, reliability, maintainability, compliance, and auditability.

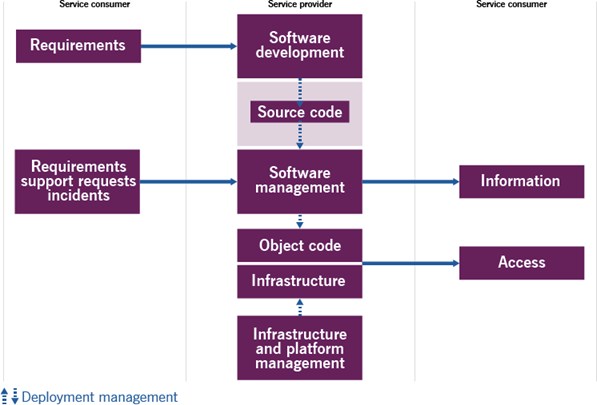

The software development and management practice focuses on the development and management of application software. However, many of the principles are also applicable to the software that is part of the infrastructure on which applications are developed and managed. Software engineering is increasingly important for infrastructure and platform management, for example in the application of Infrastructure as Code. This concept uses machine-readable definition files to manage and provision IT infrastructure and platforms, instead of physically configuring hardware components.

Software development and management covers the whole lifecycle of applications. This can vary from several months to several decades and is on average 10 to 15 years. From an economic perspective, historically on average 20% of the total costs of ownership of an application was spent on development as opposed to management, and 20% of software management costs is related to corrective maintenance.

In the modern world bigger shares of an application’s total costs of ownership shifts to development. Since constant changes become an integral part of the application lifecycle, all maintenance activities can become a part of development and are usually not referred to as maintenance.

2.2 TERMS AND CONCEPTS

2.2.1 Environments

The deployment management practice enables the move of products, services, and service components between the environments.

Software

A set of instructions that tell the physical components (hardware) of a computer how to work. Software manifests itself in applications for end users but also in the underlying infrastructure that is needed to develop and operate applications. Software and infrastructure are service components that are combined with other service components or resources to form products and services.

Software is a crucial part of business. It can provide value to customers through technology- enabled business services. Software development becomes critical as most modern services become not software-aided, but software-enabled.

Software Development

The design and construction of applications according to functional and non-functional requirements and correction and enhancement of operational application according to changing functional and non-functional requirements.

The trend to outsource software development services has been reversed in recent years, with many organizations taking critical and strategic development back in-house. This includes banks, insurance and retail companies.

Maintenance

The modification of the application as part of development, for both correction and enhancement purposes:

corrective: correcting defects in the application that have caused incidents

preventive: preventing defects in the application before they have manifested themselves

adaptive: adapting the application to work with changed infrastructure

perfective: enhancing the functionality, usability and performance of the application (sometimes known as ‘additive maintenance’, ‘enhancement’ or ‘development’

With the rate of change modern services are experiencing, services become ever-changing. It is usual for the modern application to be modified throughout its lifecycle. This means that all the activities which used to form maintenance are now part of development process.

Software management is a broader term, potentially referring to application strategy and planning, operation, safekeeping of the application artefacts and application decommissioning.

The purpose of the practice states that applications should meet internal and external stakeholder needs, in terms of functionality, reliability, maintainability, compliance, and auditability. All the terms mentioned describe software quality.

Software quality

A qualification of the value of software as a product and in its use. A common categorization (ISO/IEC 25010:2011) is:

product quality: functional suitability, performance efficiency, compatibility, usability, reliability, security, maintainability, and portability

quality in use: effectiveness, efficiency, satisfaction, freedom from risk, and context coverage.

Quick-fixes are often preferred to proper but time-consuming changes. The high rate of change in software may lead to an accumulated amount of rework that will have to be done at some point, known as a technical debt.

Technical debt

The total rework backlog accumulated by choosing workarounds instead of system solutions that would take longer. In case of software development and management, it’s total amount of rework needed to repair substandard (changes to) software.

For many practitioners involved in software development and management the main watershed lies in how Agile the chosen software development lifecycle (SDLC) model is.

SDLC model

The sequence in which the stages of the software development lifecycle are executed. The major stages are:

-establish requirements

-design

-code

-test

run/use the application.

waterfall model: each stage of the development lifecycle is executed in sequence, resulting in a single delivery of the whole application for use.

incremental model: after the requirements and priorities for the whole application have been established the application is developed in parts (builds). For each build, each of the further stages of the development lifecycle is executed in sequence. Builds can be (partially) developed in parallel, and the application is delivered in useable parts.

iterative or evolutionary model: after the requirements and priorities for the whole application have been partially established, the application is developed in separate builds such as in the incremental model, but because the requirements could not be fully established at the start, the design, coding, testing or the use of a build may lead to refinement of the requirements, leading to refinement of part of the application in another build.

Agile and Scrum approaches are a combination of incremental and iterative, focusing on close collaboration with the owner of the application in order to obtain fast feedback and achieve quick development of small increments from which the owner can derive value.

Scrum

An iterative, timeboxed approach to product delivery that is described as ‘a framework within which people can address complex adaptive problems, while productively and creatively delivering products of the highest possible value’ (The Scrum Guide by Ken Schwaber and Jeff Sutherland, updated November 2017).

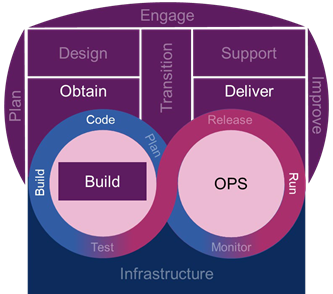

DevOps approaches further improve throughput by speeding up the transition from coding to run/use, using techniques such as continuous integration/continuous delivery to (partially) automate the deployment pipeline.

Many Agile approaches use ‘definition of done’ as a tool to agree the set of criteria to be met before the product or product increment/backlog item is considered done.

Definition of done

The agreed criteria for a proposed product of service, reflecting functional and non-functional requirements

2.3 SCOPE

The scope of software development and management is defined in terms of activities and the resources affected by the activities.

The activities supported by the software development and management practice include:

- application development

- software and software artefacts management

- operating the application (in close collaboration with infrastructure and platform management).

The resources within the scope of the software development and management practice are the concrete application artefacts within the various environments that are used. The major application artefacts are specifications, designs, source code, object code, and documentation.

In terms of responsibilities, the software development and management practice is positioned between:

- the owners of the application, who determine the requirements for development and/or management

- infrastructure management, that (a) provides the environments for software development and management and (b) manages the production environment in which software management operates the applications

- users that require support regarding the use of applications

- software management organizations that:

- were previously tasked with management of the application and are involved with onboarding of an application

- are tasked with the future management of the application and are involved with offboarding of an application.

There are many activities and areas of responsibility that are not included in the software development and management practice, but they are still closely related. These are listed in table 2.1, with references to the practices in which they can be found. It is important to remember that ITIL practices combine value chain activities through value streams to deliver value.

Table 2.1 Related activities described in other practice guides

| Activity | Practice guide |

|---|---|

| Software architecture | Architecture management |

| Utility and warranty requirements | Business analysis |

| Deployment of application artefacts from one environment to another | Deployment management |

| Providing interface for feedback from users | Service desk |

| Application portfolio management | Portfolio management |

| Making applications available for use and enabling users | Release management |

| Validating that application meets the requirements Testing the potentially releasable application | Service validation and testing |

| Orchestrating overall design for applications | Service design |

| Application monitoring | Monitoring and event management |

2.4 PRACTICE SUCCESS FACTORS

Practice Success Factor (PSF

A complex functional component of a practice that is required for the practice to fulfil its purpose.

A PSF is more than a task or activity; it includes components from all four dimensions of service management. The nature of the activities and resources of PSFs within a practice may differ, but together they ensure that the practice is effective.

The software development and management practice includes the following PSFs:

- agree and improve an organization’s approach to development and management of software

- ensure that software continually meets organization’s requirements and quality criteria throughout its lifecycle.

The first PSF is about selecting the appropriate approach and the second one about applying it.

2.4.1 Agree and improve an organization’s approach to development and management of software

There are various ways of developing and managing software, as described in SLDC model (2.2). These are waterfall, incremental, and iterative (or evolutionary). Agile and Scrum approaches are a combination of incremental and iterative.

It is a prerequisite for the software development and management practice that multiple approaches are available. These reflect the variety of situations that are expected to occur. This strategic decision also involves other practices, for example architecture management, business analysis, change enablement, release management, deployment management, information security management, portfolio management, risk management, service validation and testing, and strategy management. The decision is therefore taken in the context of the (service) value streams in which these practices are applied.

This Practice Success Factor for software development and management concerns itself with the tactical decision to select from this pre-defined set of approaches, the best approach for each software product, based on the organization’s requirements for the product.

This tactical choice depends on how much information is available about both the work to be completed and the resources that are needed to execute the work. The work to be completed can be subdivided into the requirements and the priority with which they must be fulfilled. Depending on the how much information is available about the requirements, priorities, and required resources, an appropriate approach can be selected.

Some examples:

- A waterfall approach can be an effective choice when the requirements and priorities are known, and when it is also known how to develop the software, and which resources are needed.

- A timeboxing approach in which the most important work items are developed first, could be a

better choice when the requirements and priorities are known, but it is not yet known how to develop the software and which resources are needed.

better choice when the requirements and priorities are known, but it is not yet known how to develop the software and which resources are needed.

- When the requirements and priorities are known at a high level but are difficult to finalise, a

linear iterative approach would allow the product owner to experience and refine the product across several iterations.

- Parallel experimentation may provide the product owner with prototypes that help formulate

the requirements when the requirements are ambiguous or even unarticulated.

Different approaches require different combinations of resources. These resources span all four dimensions of service management and are addressed in sections 3 to 6 of this document.

Commonly encountered combination of resources:

- Small, relatively independent, multi-functional, product-based development/maintenance teams in which a product owner manages the priority of the work to be done.

- Platform-based teams that support the development/maintenance teams with the

(self-)provision of the required infrastructure for development/maintenance and production.

- Version control tooling that tracks all production artefacts (e.g. code and documentation).

- Automated processes for continuously integrating and delivering/deploying software.

Several practices are involved in realizing this PSF. The requirements for the approach from the software development and management practice emerge in the form of organizational performance information and improvement opportunities. These transformed into improvement initiatives and plans (continual improvement practice). The plans are executed (organizational change management practice), resulting in various approaches and resources that can be applied according to the characteristics of the work to be done (software development and management practice).

2.4.2 Ensure that software continually meets organization’s requirements and quality criteria throughout its lifecycle

Software quality is used to describe software as a product and in its use, commonly in terms such as:

- product quality: functional suitability, performance efficiency, compatibility, usability, reliability, security, maintainability, and portability

- quality in use: effectiveness, efficiency, satisfaction, freedom from risk, and context coverage.

In the ISO/IEC 25010:2011 standard, each of these characteristics comprises up to six sub-characteristics

that help to specify the desired properties of the software. They can also be regarded as utility

requirements (e.g. functional suitability and usability) and warranty requirements (e.g. performance efficiency and maintainability).

After the initial development, maintenance is affected by the realised maintainability of the software. Understanding the software typically represents half of the maintenance effort, so maintainability influences the speed and cost of maintenance.

Maintenance is not only influenced by maintainability but also influences it. The quality of software tends to degrade (‘software entropy’) unless an effort is made to maintain it. This investment limits technical debt (the rework needed to repair substandard changes to software).

Many of the requirements for these software quality characteristics are input for software development and management. They are determined by the owner of the software. However, some characteristics are not the primary concern of software development and management. For example, effectiveness is determined by the users’ understanding of the software and how they use it and the information or devices that the software enables.

The most important components of this Practice Success Factor are:

- understanding the source code, how the various modules are interrelated, and the application architecture

- understanding the requirements and the context in which the application is used

- ensuring that non-functional (warranty) requirements are included in the Definition of Done

- creating tests before coding

- effective version control of all application artefacts

- approaching the task of coding with a full appreciation of its tremendous difficulty and respecting the intrinsic limitations of the human mind1

- adhering to coding conventions

- peer review

- fast feedback from testing, for example by using automated testing, and taking remedial action quickly.

Software development and management is not the only practice involved. Realising this PSF also entails establishing the right requirements for the software (business analysis), testing whether the software complies with these requirements (service validation and testing), running the software on the production infrastructure (infrastructure and platform management), formulating problem reports (problem management), etc. The metrics must therefore be regarding in this broader context.

2.5 KEY METRICS

The ITIL practices are means, or tools, for the management of products and services. Like the performance of any tool, practice performance can be assessed only in the context of that tool’s application. However, tools can differ in quality. This difference defines the tool’s potential or capability

1 Dijkstra, E.W. The Humble Programmer (1972) www.cs.utexas.edu/~EWD/transcriptions/EWD03xx/EWD340.html [Accessed 29th October 2019]

Table 2.2 Example metrics for the practice success factors

| Practice success factors | Example metrics |

|---|---|

| Agree and improve an organization’s approach to development and management of software | -Stakeholders’ satisfaction with the approach chosen for software development and management -Percentage of the development teams following the chosen approach -Stakeholders’ satisfaction with the rate of change allowed by the chosen approach -Improvement initiatives throughput for the software development and management practice -Approach compliance to the internal and external requirements, policies and legislation. |

| Ensure that software continually meets organization’s requirements and quality criteria throughout its lifecycle | -Stakeholder satisfaction with the applications delivering the value -Applications compliance with internal and external requirements and policies -Frequency of delivery of software (for new or changed functionality) -Speed of delivery of software (from receipt of specifications to code committed to the repository and released for deployment) -Reliability of delivery of software (defects detected after release for deployment) -Cost (per function point or other unit of size; decreasing cost) -Technical debt (estimated cost of rework to repair substandard (changes to) software) -Resource utilization (compute, network, storage) -Availability of software (MTTR, MBTF) -Security breaches and costs related to audits etc. |

The correct aggregation of metrics into complex indicators will make it easier to use the data for the ongoing management of value streams, and for the periodic assessment and continual improvement of the deployment management practice. There is no single best solution. Metrics will be based on the overall service strategy and priorities of an organization, as well as on the goals of the value streams to which the practice contributes.

3. Value Streams and processes

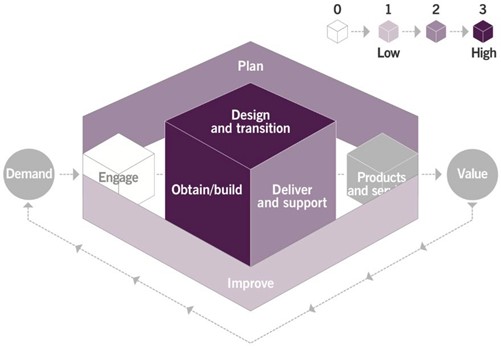

3.1 VALUE STREAM CONTRIBUTION

Like any other ITIL management practice, software development and management contribute to multiple value streams. Remember, no value stream is made up of a single practice. Software development and management combines with other practices to provide high-quality services to consumers. The main value chain activities to which software development and management contributes are:

- obtain/builddeliver and support

3.2 PROCESSES

Each practice may include one or more processes and activities that may be necessary to fulfil the purpose of that practice.

Definition: Process

A set of interrelated or interacting activities that transform inputs into outputs. A process takes one or more defined outputs and turns them into defined outputs. Processes define the sequence of actions and their dependencies.

There are numerous models to structure processes of the software development and management practice. These span several decades and range from waterfall, such as the V-model or the Winston W. Royce’s model, to iterative and incremental ones, such as Agile and Spiral approaches.

A service provider organization normally combines vastly different approaches to achieve the most efficient and manageable set of repeatable processes. However, a set of activities common among the majority of practical approaches can be identified for the purposes of this publication.

Table 3.1 Inputs, activities and outputs of the software development and management practice

| Input | Activities | Output |

|---|---|---|

| Business case, business logic requirements, service models, architecture documents, user stories, tasks, defects in the existing backlog and project plan | Product planning and prioritization | New backlog/project tasks, project or change delivery plan |

| Relevant backlog\project items | Software design | Technical requirements for new or changed software. |

| Existing environment configuration | New code production | Application code, test cases, automated unit tests |

| Existing development toolset and version tracking methods | Code review | Updated code, new backlog items |

| User feedback on applications | Defect handling | Meeting agendas, meeting minutes, schedules, meeting minutes, decisions and new rules, action plans |

| Technical standards for application development. | Technical debt management | Software pipeline, monitoring, and maintenance automation tools |

| Code refactoring | Updated development environment configuration | |

| Research and Development | New versions ready for deployment, software change record keeping | |

| Regular meetings and improvement activities | New/proposed changes to architectural decisions | |

| Software operation and maintenance automation | Information about the value of the software | |

| Managing development environments | Release notes about the software being developed: technical documents and user documentation (how to use, install, configure); administration documentation (how to manage) | |

| Version Control. | New/proposed changes to technical standards. | |

4. Organizations and people

4.1 ROLES, COMPETENCIES, AND RESPONSIBILITIES

The practice guides do not describe the practice management roles such as practice owner, practice lead or practice coach. The practice guides focus on specialist roles specific to each practice. The structure and naming of each role may differ from organization to organization, so any roles defined in ITIL should not be treated as mandatory, or even recommended. Remember: roles are not job titles. One person can take on multiple roles and one role can be assigned to multiple people.

Roles are described in the context of processes and activities. Each role is characterized with a competence profile based on the following model:

Table 4.1 Competency codes and profiles

| Competence code | Description |

|---|---|

| L | Leader Decision-making, delegating, overseeing other activities, providing incentives and motivation, and evaluating outcomes |

| А | Administrator. Activities and skills associated with this competence include the assignment and prioritization of tasks, record keeping, ongoing reporting, and basic improvement initiatives. |

| C | Coordinator/communicator. Activities and skills associated with this competence include the coordination of multiple parties, communication between stakeholders, and the running of awareness campaigns. |

| М | Methods and techniques expert. Activities and skills associated with this competence include the design and implementation of work techniques, the documentation of procedures, consulting on processes, work analysis, and continual improvement. |

| Т | Technical expert. This competence focuses on technical (IT) expertise and expertise-based assignments. |

4.1.1 Roles involved in the software development and management activities

Examples of roles which can be involved in the software development and management practice activities are listed in table 4.1, together with the associated competence profiles and specific skills.

Table 4.1 The roles involved in the software development and management activities

| Activity | Responsible roles (examples) | Competency profile | Specific skills |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product planning and prioritization | Project manager Product owner | CMLT | Good knowledge of business objectives Good command of project management practices and other relevant delivery methods |

| Software design | Business analyst Or Software developer | TM | Technical development and analysis tools specific to software |

| New code production | Software developer | TM | Technical development and analysis tools specific to software |

| Defect handling | Software developer | TM | Technical development and analysis tools specific to software |

| Technical debt mitigation | Software developer | TM | Technical development and analysis tools specific to software |

| Code review | Software developer | TM | Technical development and analysis tools specific to software |

| Code refactoring | Software developer | TM | Technical development and analysis tools specific to software |

| Research and development | Software developer | TMC | Technical development and analysis tools specific to software |

| Regular meetings and improvement activities | Software development team leader, Product owner, software developers, business analysts, Testing engineers, Scrum master | CLT | Technical development and analysis tools specific to software |

| Software operation and maintenance automation | Software developer | TMC | Technical development and analysis tools specific to software Understanding of software operations and nature of the manual activities required to maintain and operate the software. |

| Managing development environments | Software development team leader, software developers, infrastructure engineer | MTC | Good knowledge of controlled environment configuration |

| Version control | Software development team leader, software developers | MTC | Good knowledge of software version tracking approaches |

4.1.2 Software developer/team member

The key role for the software development and management practice is the developer, or an engineer. This is the most common type of a knowledge worker in the IT field. The algorithmic thinking is a core of the skillset for a software developer. Other aspects of the core software developer knowledge and skill set are:

- programming languages, environments, and technologies

- object oriented software design

- contemporary system architectures, such as Event Driven Architecture (EDA)

- software testing approaches and methods

- problem-solving techniques.

However, a modern software developer needs to have a strong command of a broad spectrum of technical and communication competencies:

- knowledge of technologies adjacent to the technology stack that they work in

- techniques to plan and priorities activities, decisions, and risk mitigation measures within their scope of control, be it themselves, or the team they manage

- skills in interpersonal, bi-directional, and broadcasting communications, including ability to highlight issues, transfer ideas and concepts, and document and present the solutions

- continuous learning ability to keep up with the pace of technology evolution.

There are also a set of personal traits that a software developer must maintain and harness:

- Willingness to quickly advance on a problem resolution journey to explore new possibilities, to experiment, and to take reasonable risks (see for example the OODA Loop approach, High- velocity IT).

- Eagerness to review what has been done, such as bug fixing, code refactoring, legacy software maintenance, and technical debt tasks.

- Systemic approach to the operations tasks, with an outlook to automate deployment, maintenance, backup, monitoring and other mundane chores related to operating of the software.

- Agility in teamwork approach, where software developers migrate between teams, products, or projects, which is especially crucial in commercial and large-scale service provider organizations.

4.1.3 Software team leader

It is common for a software developer to go through a career progression from a junior developer, dealing with elementary tasks of low risk, to a senior developer with more experience around a specific product and underpinning technologies. A senior developer can be the key knowledge bearer other development team members seek for advice.

One career path open to a senior developer is a team leader, colloquially known as a ‘team lead’ role. A team leader can in some organizational environments carry a managerial designation (especially in traditional teams) but is first and foremost a servant leader for their team of developers (read more on Servant Leadership in High-velocity IT and Create, Deliver and Support).

The primary task of a team leader is to be an effective liaison for their software development team within a broader business or service provider context. Apart from skills and behaviours listed for a software developer, the following should be prominent in a team leader:

- understanding of the business problem the software is solving

- understanding of impediments their team is facing

- understanding of the service provider context and value streams that the service provider which the development team is part of owns

- understanding of the business context the software is going to be used in

- understanding of other disciplines like management, product development, marketing, etc.

- negotiation techniques

- motivation and incentivizing of the personnel techniques.

There are further roles within a software development and management organization with progressively expanding scope of control, such as tech lead, development managers, etc. See section 4.2 Organizational structures below.

4.1.4 Scrum master/Agile coach

A Scrum master is a colloquial term originating from the Scrum Guide by Jeff Sutherland and Ken Schwaber (see https://www.scrumguides.org). This role normally represents a coaching discipline in an Agile environment. The scrum master is there to ensure that an agile way of working is adhered to by all staff involved. This objective can be realized in a variety of ways, from purely consulting and communication tasks to a subset of the servant leadership and management tasks. In the latter case naturally the team leader takes upon responsibilities of a scrum master.

The importance of coaching originates from the fact that Agile methods require foundational changes to the habits and traditions around how the services and products are delivered. Coaching helps team members develop and maintain new behaviours and attitudes, as well as promote the visibility of the outcomes of all team activities. The coaching for example is the foundation of suggested Toyota Kata continual improvement practice (see 3.4.3 High-velocity IT)Read more on the culture shift that modern agile service provider environments require in High- velocity IT (3. High-velocity IT culture) and in Create, Deliver and Support (2.3 Developing team culture).

4.1.5 Product owner

This is a role external to the software development and management team, but which is paramount to its success. The product owner is generally defined in some agile frameworks as the person ultimately responsible for business results. There are parallels in a traditional organizational set up, such as project managers, or even service owners.

The software development and management practice may be realised in a service provider organization in a variety of ways, including agile frameworks such as Scrum. It is crucial therefore to define a single authority for the development team to turn to for prioritization of its work, and for external escalations. Therefore, this role is the pivotal point to enable correct interfaces between the development team and other parts of service provider and service consumer organizations.

4.2 ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES AND TEAMS

However talented or productive, a single development team can rarely satisfy all the demand for new or updated services. As the size of a team is conventionally defined around natural ability to manage directly, i.e. 5 to 7 staff per manager, the number of development teams is a primary organizational variable, determining the human resource investment in the software development and management practice.

Although all software development and management teams perform similar activities, they can be grouped together differently, depending on relative importance of software products in the service offerings and on overall organizational design, for example:

- the purpose and functionality of the software

- the functionality of the software

- the platform on which the software runs

- the type or brand of technology used.

One example is product teams: a relatively self-contained, multi-disciplinary and multi-tasking development/management team that exists for as long as the application (the ‘product’) exists; this is an alternative to temporary project-based teams that are formed to execute a project and are then disbanded. Work is executed in more consistently than in the project-based scenario.

By the end of the 20th century, application development and management departments within internal and commercial IT service providers acted mostly as independent units, at times even as parts of different entities. The disconnect between the two has not been dissimilar to the traditional project vs operations silos. However, more recently these two departments are being brought together, experiencing greater pressure from the business to be more responsive and cooperative. The DevOps model caters for such integration, suggesting that the onus is on developers to ensure automated and error-prone deployment of software and its ongoing operation and maintenance.

5. Information and technology

5.1 INFORMATION EXCHANGE

Effective information exchange is essential for the success of the software development and management practice. It is important to note that each development team rarely acts independently by delivering a full-scale software product, but rather contributes constituent parts to service offerings. Such team depends on outputs from other teams (such as infrastructure and platform management) and produces outcomes likely used by other development team (for example reusable code libraries) and further steps in value streams (such as quality assurance or deployment).

Requirements, support requests, and incidents are the primary input for software development and management, and access to and information about the operational application are the primary output.

It is important information exchange is clear and reliable. It should be designed to be efficient both among team members, possibly widely distributed geographically, and also with external teams.

At the core of almost every activity in the software development and management practice is the concept of an item in a backlog.

Depending on specific toolset or a method in use, the items can bear different names and taxonomies. A hierarchical roll-up groupings, such as ‘epic’ or ‘themes’ can be in use in development environments where hundreds and thousands of items are in progress simultaneously. In some cases, items of different nature can even have different life stages and progress conditions. And large development and product-focused organisations can adopt a hierarchy of backlogs to distribute and control items flow.

It is nevertheless generally accepted that items of a backlog should be processed in a unified lean manner, much like the value stream method suggests. The development team should plan the work, look for bottlenecks, and focus its activities and information exchange on the value it delivers.

An agreed amount of documentation must be produced to support:

- ongoing development

- operations

- use.

This documentation is in addition to temporary design documentation, which describes what needs to be created or modified.

5.2 AUTOMATION AND TOOLING

Software-related activities benefit greatly from information management tools that underpin them. Table 5.1 below suggests specific tools for each of the activities.

Table 5.1 Automated solutions for software development and management activities.

| Activity | Means of Automation | Key Functionality | Impact on Practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product planning and prioritization | Task and workflow tracking toolset Project management toolset | Work scheduling and visualization | High |

| Software design | Development toolset, development environments | Collaboration and automated design | High |

| New code production | Development toolset, development environments | Code management | High |

| Code review | development toolset, development environments | Code management | High |

| Defect handling | Development toolset, development environments | Code management | High |

| Technical debt mitigation | Workflow and task tracking systems, Known errors database, Development toolset, development environments | Code management | High |

| Technical debt mitigation | Workflow and task tracking systems, Known errors database, Development toolset, development environments | Code management | High |

| Code refactoring | development toolset, development environments | Code management | High |

| Research and Development | Development toolset, development environments | Code management | High |

| Regular meetings and improvement activities | Development toolset, development environments | Collaboration and scheduling; record keeping | Medium |

| Software operation and maintenance automation | Remote administration tools, configuration management tools, automated deployment systems, development toolset, development environments | Scripted task automation and scheduling, infrastructure orchestration | High |

| Managing development environments | Configuration management toolset, development environments | Infrastructure orchestration | High |

| Version Control | Development toolset, development environments | Code repository management | High |

6. Partners and suppliers

Very few services are delivered using only an organization’s own resources. Many organizations often depend on services provided by third parties (see ITIL® Foundation: ITIL 4 Edition section 2.4 for a model of a service relationship).

Development teams represent a highly specialised capability that most organisations would not have suitable means to manage. It is common for contemporary internal service providers to outsource the software development and management capabilities to third parties. When either or both development and management of business applications and other software is sourced commercially, the service provider management should consider all complexities that accompany defining what good output from that external provider must look like.

There are several important quality criteria that need to be negotiated, agreed, and defined in the respective software sourcing contract:

- The definitions of service. As obvious as it can be, the exact and explicit definition of the service offerings for a development and management contract is an absolute must. The activities within this practice provide an overall range of things that a development team can do in order to ensure software quality. That list is not limited to simple new coding and bug-fixing but encompasses whole software lifecycle. The parties should consciously negotiate the required activities from the range and consider both pricing, and partnership benefits that are most important to both.

- People and organisations. The parties must agree on the organizational structure, expected

knowledge transfer mechanisms, expected turnover rates, vetting principles, and geographical location of the staff that will populate the development teams.

- Value streams and processes. The parties must agree on how the external development teams

should interact with others. This is especially important, where some development and management capabilities are retained within the service provider and external teams will need to be compliant to two sets of controls: one within the supplier organization, i.e. their employer, and another one within the service provider, i.e. the client organization. Examples of clashes that can occur are abound: from simple burden of double record keeping and backlog grooming (borderline waste), to complications during availability planning. The work of service owners (or product owners in an agile environment) becomes pivotal in analysing the external development team involvement in value streams.

- Information and technology. The parties must clearly define the single systems of record for the

purpose of the contract, as mentioned above, there is little merit in making the development teams spend time in duplicating defect records in their ‘native’ and external systems. The information security considerations and onboarding of new staff are also something to be covered explicitly in the agreement.

Arguably a systemic cost-benefit analysis yields results quite different from an intuitive expectation that external specialised development teams are always ‘cheaper’ and ‘more effective’ than internal teams. The additional benefits expected in the short term have no long- term guarantee, simply because of the speed and emerging nature of software development. That rate of change in practices, architectures, and user expectations may require capabilities that an external supplier might not be willing to deliver.

7. Important reminder

Most of the content of the practice guides should be taken as a suggestion of areas that an organization might consider when establishing and nurturing their own practices. The practice guides are catalogues of things that organizations might think about, not a list of answers. When using the content of the ITIL Practice guides, organizations should always follow the ITIL guiding principles:

- focus on value

- start where you are

- progress iteratively with feedback

- collaborate and promote visibility

- think and work holistically

- keep it simple and practical

- optimize and automate.

More information on the guiding principles and their application can be found in section 4.3 of the

ITIL® Foundation: ITIL 4 Edition publication.