1. About this document

It is split into five main sections, covering:

- general information about the practice

- the practice’s processes and activities and their roles in the service value chain

- the organizations and people involved in the practice

- the information and technology supporting the practice

- considerations for partners and suppliers for the practice.

1.1 ITIL® 4 QUALIFICATION SCHEME

Selected content of this document is examinable as a part of the following syllabus:

- ITIL Specialist: Create, deliver and support

- ITIL Specialist: High Velocity IT

Please refer to the syllabus documents for details.

2. General information

2.1 PURPOSE AND DESCRIPTION

Key message

The purpose of the incident management practice is to minimize the negative impact of incidents by restoring normal service operation as quickly as possible.

Normal service operation is typically defined within service level agreements (SLAs), or other forms of service quality specification, as that which may be agreed internally by the service provider. The specification can include more quality criteria than were initially agreed with the customers. Consequently, the incident management practice includes the restoration of the normal operation of services and resources, even when their failure or deviation is not visible to the service consumers. In this case, normal operation is defined in configuration items (CIs) or service technical specification. However, an expert opinion may be used to assess the status of the resources and services if there is no documented specification of a normal operation. When required, the incident management practice can be used to correct the faulty resource or service.

The incident management practice is a fundamental element of service management. The quick restoration of a service is a key factor in user and customer satisfaction, the credibility of the service provider, and the value an organization creates in the service relationships.

2.2 TERMS AND CONCEPTS

Incident

An unplanned interruption to a service or reduction in the quality of a service.

The incident management practice ensures that periods of unplanned service unavailability or degradation are minimized, thus reducing negative impacts on users. There are two main factors enabling this: early incident detection and the quick restoration of normal operation.

The quick detection and resolution of incidents is made possible with effective and efficient processes, automation, and supplier relationships alongside skilled and motivated specialist teams. Resources from the four dimensions of service management are combined to form the incident management practice.

Some systems and services demonstrate patterns of operations that include so-called typical incidents. These may be associated with known errors, such as a lack of compatibility or patterns of incorrect user behaviour. Service providers often define incident models to optimize the handling and resolution of repeating or similar incidents. These help to resolve incidents quickly and efficiently, often with better results due to the application of proven and tested solutions.

Definition: Incident model

A repeatable approach to the management of a particular type of incident.

The creation and use of incident models are important activities in the incident management practice. This is described further in section 3.

Although some incidents have a relatively low impact on service operation and consumption, others lead to dramatic consequences for service consumers and the service provider. These are called major incidents and require special attention.

Definition: Major incident

An incident with significant business impact, requiring an immediate coordinated resolution.

A significant business impact is not the only characteristic of a major incident. For instance, when there are multiple systems and services designed for high availability usage, single failures are unlikely to cause a significant business impact. Failures will be quickly, and often automatically, detected and fixed. Major incidents are often associated with a higher level of complexity. For example, if multiple seemingly trivial events coincide, it can escalate and have an impact on service consumers. Complex incidents such as this require a special approach to management and resolution. It would be beneficial to implement a model to manage all incidents, even though major incidents rarely recur and usually differ in nature. A model for a major incident may include:

- a clear criteria to distinguish major incidents from disasters and other incidents

- a special accountable coordinator, sometimes referred to as the major incident manager (MIM)

- a dedicated temporary team created to investigate and resolve a major incident

- other dedicated resources (including budget); for example, for urgent consultations with third- party experts or procurement of components

- special methods of investigation (for example, swarming)

- an agreed model of communications with users, customers, regulators, media, and other stakeholders

- an agreed procedure for review and follow-up activities.

Definition: Workaround

A solution that reduces or eliminates the impact of an incident or problem for which a full resolution is not yet available. Some workarounds reduce the likelihood of incidents.

Sometimes, it may be impossible to find a system solution for an incident. In these situations, service providers may apply a workaround.

Workarounds promptly restore the service to an acceptable quality. However, workarounds can increase technical debt and may lead to new incidents in the future. The problem management practice can be used to reduce the technical debt created by incident workarounds. In many cases, understanding the cause or causes of an incident can help find an optimal solution.

Definition: Technical debt

The total rework backlog accumulated by choosing workarounds instead of system solutions that would take longer.

2.3 SCOPE

The scope of the incident management practice includes:

- detecting and registering incidents

- diagnosing and investigating incidents

- restoring the affected services and CIs to an agreed quality

- managing incident records

- communicating with relevant stakeholders throughout the incident lifecycle

- reviewing incidents and initiating improvements to services and to the incident management practice after resolution.

There are a number of activities and areas of responsibility that are not included in the incident management practice, although they are still closely related to it. These activities are listed in Table 2.1, along with references to the practice guides in which they can be found. It is important to remember that the ITIL practice guides are merely collections of tools to use in the context of value streams and should be combined as necessary, depending on the situation.

Table 2.1 Activities related to the incident management practice that are described in other practice guides

| Activity | Practice guide |

|---|---|

| Investigating causes of incidents | Problem management |

| Communicating with users | Service desk |

| Implementation of changes to products and services | Change enablement Deployment management Infrastructure and platform management Project management Release management Software development and management |

| Monitoring technology, teams, and supplier performance | Monitoring and event management |

| Management of improvement initiatives | Continual improvement |

| Management and ful filment of service requests | Service request management |

| Restoring normal operations in case of a disaster | Service continuity management |

2.4 PRACTICE SUCCESS FACTORS

Practice success factor

A complex functional component of a practice that is required for the practice to fulfil its purpose.

A practice success factor (PSF) is more than a task or activity; it includes components from all four dimensions of service management. The nature of the activities and resources of PSFs within a practice may differ, but together they ensure that the practice is effective.

The incident management practice includes the following PSFs:

- detecting incidents early

- resolving incidents quickly and efficiently

- continually improving the incident management approaches.

2.4.1 Detecting incidents early

Previously, it was common practice to register most incidents based on information from end users and IT specialists. This method of sourcing information is still widely used, but good practice currently suggests detecting and registering incidents automatically. This can be done immediately after incidents occur and before they start affecting users. This approach has multiple benefits that includes the following:

- Earlier incident detection decreases the time of service unavailability or degradation.

- The higher quality of the initial data supports the correct response and resolution of incidents, including automated resolution, otherwise known as self-healing.

- Some incidents remain invisible to users, improving user satisfaction and customer satisfaction.

- Some incidents may be resolved before they affect the service quality agreed with customers, improving the perceived service and the formally reported service quality.

- Costs associated with incidents may decrease.

The detection of incidents is enabled by the monitoring and event management practice. This includes tools and processes for event categorization that distinguishes incidents from information events and warnings.

Automatically detected incidents can be categorized either automatically, manually, or part- automatically. A part-automatic categorization is made manually but is based on suggestions made by the system. Automated incident detection and categorization may benefit from machine learning solutions, using the data available from past incidents, events, known errors, and other sources.

When automated incident detection is not possible, incidents are usually detected when they have already impacted users and their work. Even then, the earlier an incident is reported and registered, the better. This can be achieved by promoting a culture of responsible service consumption among users that includes encouraging the reporting of suspicious events and behaviour, and tolerating false reports, within reason.

2.4.2 Resolving incidents quickly and efficiently

This PSF is vital for the success of the incident management practice and for general service quality. After incidents are detected they should be handled effectively and efficiently, considering the complexity of the environment:

- In simple situations, such as recurring and well-known incidents, pre-defined resolution procedures are likely to be effective. These may include automated resolution or standardized routing and handling (according to an appropriate pre-agreed incident model).

- In complex situations, where the exact nature of the incident is unknown but the systems and

components are familiar to the support teams and the organization has access to expert knowledge, incidents are usually routed to a specialist group or groups for diagnosis and resolution. Sometimes this can assist in identifying patterns and lead to a model and/or a solution which can be applied to similar incidents in the future.

- In very complex situations, where it is difficult or impossible to define an expert area and

group, or where defined groups of experts fail to find a solution, a collective approach may be useful. This technique is known as swarming.

Swarming

A technique for solving various complex tasks. In swarming, multiple people with different areas of expertise work together on a task until it becomes clear which competencies are the most relevant and needed.

Usually, swarming assists in decreasing the level of complexity and makes it possible to switch to the techniques used in a less complex environment. Nonetheless, swarming is usually applied to major incidents of an unknown nature. In these situations, pulling together numerous specialized resources is cost-effective compared to the losses resulting from the incident remaining unsolved.

Physical meetings are not required when swarming. When a plan is established, experts may work alone to complete experiments, design scripts, and use other tools to discover what is happening. To engage with the incident, swarming utilizes the correct people rather than a great amount of people.

Other techniques can be used in complex situations. For example, expert analysis may be replaced or combined with a series of safe-to-fail experiments which aim to improve the understanding of

the nature of the incident. A complexity-based framework for decision-making1 is useful for dealing with incidents in environments of high and changing complexity.

Regardless of the complexity, it is important to confirm the high quality of the incident data from the first steps of incident handling. This has a strong influence on the:

- correctness of the decisions made

- speed of service recovery

- effective use of resources

- ability to find and remedy the underlying cause(s)

- possibility and quality of machine learning.

2.4.1 Incident prioritization

Incidents should be resolved as soon as possible. However, the resources of the teams involved in incident resolution are limited and these teams are often simultaneously involved in other types of work. Some incidents should be prioritized to minimize any negative impacts on users.

Task priority The importance of a task relative to other tasks. Tasks with a higher priority should be worked on first. Priority is defined in the context of all the tasks in a backlog.Prioritization An action of selecting tasks to work on first when it is impossible to assign resources to all tasks in the backlog.

There are a number of simple guidelines for incident prioritization:

- Evaluating the impact and urgency of an incident (and the time constraints for its investigation and resolution) is not prioritization. However, this evaluation is useful for prioritization and other important considerations, such as estimating the amount of time needed to perform the work.

- Prioritization is needed only when there is a resource conflict. Where there are sufficient

resources to process every task within the time constraints, prioritization is unnecessary.

- Incidents should await processing in a single backlog, together with other tasks (planned and unplanned).

- Prioritization is a tool for assigning people to tasks in the context of a team. If an incident is handled by multiple teams, it will be prioritized within each team depending on resource availability, target resolution time, and estimated processing time.

1 http://cognitive-edge.com/videos/cynefin-framework-introduction

- Resource availability and estimated processing time are defined by the team. Also, the processing time may be standardized for repeating operations. The target resolution time may be defined by SLAs and/or the internal service specifications of the service provider. The impact assessment and completion (resolution) time may change as support teams discover new information.

- Visualization tools, such as Kanban, and Lean principles, such as the limiting of work in progress,

are useful for effective prioritization.

These rules apply to all types of work, whether planned or unplanned, performed by the service provider’s specialist teams. It is important that they are agreed and followed by everyone involved in the organization’s service management activities, across all practices.

2.4.3 Continually improving the incident management approaches

Periodic reviews of incidents should be conducted to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the incident management practice. Some incidents will require an individual review upon resolution. This usually applies to major incidents, new types of incidents, and incidents that were not resolved in time. Most incidents, however, do not require an individual review beyond confirming their successful resolution. Nonetheless, an overview of the incident management records at certain intervals will help to identify positive experiences and room for improvement; share knowledge between specialist teams; identify new types of incidents; and improve or introduce incident models.

Periodic reviews provide an opportunity to analyse the stakeholders’ satisfaction with the incident management practice. Periodic incident review is also key for the continual improvement of the practice and the organization’s products and services.

Key message

The importance of dataEffective reviews will always need data; therefore, it is important to agree the requirements for documenting it. Data should be:Concurrent It is useful to know exactly what was done when, to assist in continual improvement. This requires stakeholders to update incident records during, not after, the event. Also, an accurate timeline may be useful for investigating the problem.

Complete A considerable amount of activity can be hidden behind a simple statement. For example, a statement such as ‘We restarted the cluster and normal function was observed after 45 minutes’ may hide useful detail. It could mean: ‘We restarted Server 1, then 2, then 3 and found that Server 4, which was operating normally, stopped. We checked the manual and restarted Servers 2 and 4, then 1 and 3. All were processing data correctly after 10 minutes.

’Comprehensive Describing why an action was taken can be just as important as describing the action itself.

2.5 KEY METRICS

The effectiveness and performance of the ITIL practices should be assessed within the context of the value streams to which each practice contributes. As with the performance of any tool, the practice’s performance can only be assessed within the context of its application. However, tools can differ greatly in design and quality, and these differences define a tool’s potential or capability to be effective when used according to its purpose. Further guidance on metrics, key performance indicators (KPIs), and other techniques that can help with this can be found in the measurement and reporting practice guide.

Key metrics for the incident management practice are mapped to its PSFs. They can be used as KPIs in the context of value streams to assess the contribution of the practice to the effectiveness and efficiency of those value streams. Some examples of key metrics are given in Table 2.2.

In practice, metrics should be applied to a specific context such as type of incident, services, specialist groups, or periods of time. The correct aggregation of metrics into complex indicators will make it easier to use the data for the ongoing management of value streams, and for the periodic assessment and continual improvement of the incident management practice. There is no single best solution. Metrics will be based on the overall service strategy and priorities of an organization, as well as on the goals of the value streams to which the practice contributes.

Table 2.2 Examples of key metrics for the practice success factors

| Practice success factors | Key metrics |

|---|---|

| Detecting incidents early | Time between incident occurrence and detection Percentage of incidents detected via monitoring and event management |

| Resolving incidents quickly and efficiently | Time between incident detection and acceptance for diagnosis Time of diagnosis Number of reassignments Percentage of waiting time in the overall incident handling time First-time resolution rate Meeting the agreed resolution time User satisfaction with incident handling and resolution Percentage of the incident resolved automatically Percentage of incidents resolved before being reported by users |

| Continually improving the incident management approaches | Percentage of incident resolutions using previously identified and recorded solutions Percentage of incidents resolved using incident models Improvement of the key practice indicators over time Balance between speed and effectiveness metrics for incidentresolution |

3. Value Streams and processes

3.1 VALUE STREAMS CONTRIBUTION

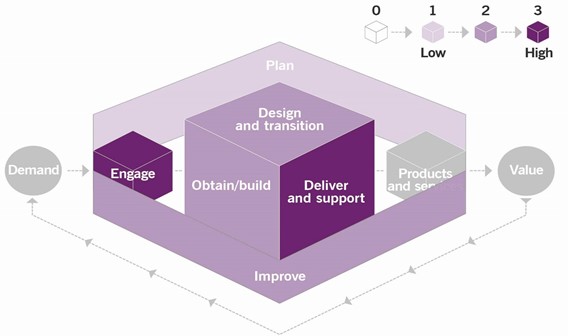

Like any other ITIL practice, the incident management practice contributes to multiple value streams. It is important to remember that a value stream is never formed from a single practice. For example, even when a value stream is focused on incident resolution, other practices are involved, such as service desk, monitoring and event management, service configuration management, change enablement, supplier management, infrastructure and platform management, and software development and management.

The incident management practice is primarily concerned with the restoration of normal systems or service operation in various work environments. The main value chain activities to which the practice contributes are:

- engage

- deliver and support

- design and transition

- improve

- obtain/build.

The contribution of the incident management practice to the service value chain is shown in Figure 3.1.

3.2 PROCESSES

Each practice may include one or more processes and activities that may be necessary to fulfil the purpose of that practice.

Process

A set of interrelated or interacting activities that transform inputs into outputs. A process takes one or more defined inputs and turns them into defined outputs. Processes define the sequence of actions and their dependencies.

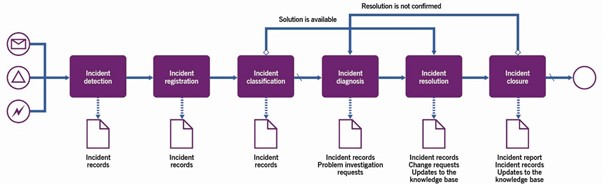

Incident management activities form two processes:

- Incident handling and resolution This process is focused on the handling and resolution of individual incidents, from detection to closure.

- Periodic incident review This process ensures that the lessons from incident handling and resolution are learned and that approaches to incident management are continually improved.

3.2.1 Incident handling and resolution

This process includes the activities listed in Table 3.1, and transforms the inputs into outputs.

Table 3.1 Inputs, activities, and outputs of the incident handling and resolution process

| Key inputs | Activities | Key outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Monitoring and event data User queries Configuration information IT asset information Service catalogue SLAs with consumers and suppliers/partners Capacity and performance information Continuity policies and plans Information security policies and plansProblem records Knowledge base | Incident detection Incident registration Incident classification Incident diagnosis Incident resolution Incident closure | Incident recordsIncident status communications Problem investigation requests Change requestsIncident reports Updates to the knowledge base Restored CIs and services |

Figure 3.2 shows a workflow diagram of the process.

Throughout the process, ownership over each incident should be ensured. The ownership may be transferred in the course of the handling and resolution process, but each incident should have a person responsible for it at any time. Also, stakeholder communications should be updated whenever there are changes in the status of the incident.

The process may vary significantly, depending on the incident model. Table 3.2 provides examples of the activities in two incident models (manual and automatic), which are just two of many options. They are meant to illustrate the difference between incident models.

Table 3.2 Activities of the incident handling and resolution process

| Activity | Manually processed user-detected incidents | Automatically detected and processed incidents |

|---|---|---|

| Incident detection | The user detects a malfunction in service operation and contacts the service provider’s service desk through the agreed channel(s). The service desk agent performs the initial triage of the user query, confirming that the querydoes indeed refer to an incident. | An event is detected by a monitoring system and identified as an incident based on a pre-defined classification. |

| Incident registration | The service desk agent performs incident registration, adding the available data to the incident record. | An incident record is registered and associated with the CI where the event has been detected. Pre-defined technical data is registered. If needed, a notification is sent to the relevanttechnical specialists. |

| Incident classification | The service desk agent performs initial classification of the incident; this helps to qualify incident impact, identify the team responsible for the failed CIs and/or services, and to link the incident to other past and ongoing events, incidents, and/or problems.In some cases, classification helps toreveal a previously defined solution for this type of incident. | Based on pre-defined rules, the following is automatically discovered:the incident’s impact on services and usersthe solutions availablethe technical team(s) responsible for the incident resolution, if automated solutions are ineffective or unavailable. |

| Incident diagnosis | If classification does not provide an understanding of a solution, technical specialist teams perform incident diagnosis. This may involve escalation of the incident between the teams,or joint techniques, such as swarming.If classification is wrong because of an incorrect CI assignment, this information should be communicated to those responsible for configuration control (see the service configuration practice guide). | If the automated solution is ineffective unavailable, the incident is escalated to the responsible technical team for manual diagnosis. It may involve escalation of the incident between the teams, or joint techniques, such as swarming.If an automated solution failed because of an incorrect CI association, this information should be communicated to those responsible for the configuration control (see the service configuration practice guide). |

| Incident resolution | When a solution is found, the relevant specialist teams attempt to apply it, working sequentially or in parallel. It may require the initiation of a change. If the solution does not work, additional diagnosis is performed. | If there is an automated solution available, it is applied, tested, and confirmed. If a manual intervention is required, a relevant specialist team attempts to apply it. It may require the initiation of a change. If the solution proves not to work, additional diagnosis is performed. |

| Incident closure | After the incident is successfully resolved, a number of formal closure procedures may be needed: -user confirmation of service restoration -resolution costs calculation and reporting -resolution price calculation and invoicing problem -investigation initiation -incident review. After all the required actions are completed and the incident records are updated accordingly, the incident is formally closed. This can be done by the product owner, service owner, incident manager, or service desk agent, depending on the agreedincident model. | If the automated solution proves effective, incident records are automatically updated and closed. A report is sent to the responsible technical team. If information about the incident has been communicated to other stakeholders at any of the previous steps, the closure of the incident should also be communicated. |

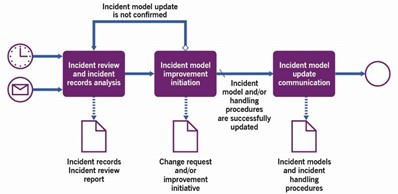

3.2.2 Periodic incident review

This process is focused on the continual improvement of the incident management practice, incident models, and incident handling procedures. It is either performed regularly or triggered by incident reports highlighting inefficiencies and other improvement opportunities. Regular reviews may take place every two to three months or more frequently, depending on the effectiveness of the existing models and procedures.

This process includes the activities listed in Table 3.3 and transforms the inputs into outputs.

Table 3.3 Inputs, activities, and outputs of the periodic incident review process

| Key inputs | Activities | Key outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Current incident models and procedures Incident records Incident reports Policies and regulatory requirements Configuration information IT asset information SLAs with consumers and suppliers/partners Capacity and performance information Continuity policies and plans Security policies and plans | Incident review and incident records analysis Incident model improvement initiation Incident model update communication | Updated incident models Updated incident handling procedures Incident records Communications about updated incident models and procedures Change requests Improvement initiatives Incident review reports |

Figure 3.3 shows a workflow diagram of the process.

Table 3.4 provides an example of the process activities.

Table 3.4 Activities of the periodic incident review process

| Activity | Example |

|---|---|

| Incident review and incident records analysis | The incident manager, together with service owners and other relevant stakeholders, performs a review of selected incidents such as major incidents, those not resolved in time, or all incidents over a certain period. They identify opportunities for incident model and incident handling procedures optimization, including the auto essing and resolution. |

| Incident model improvement initiation | The incident manager registers the improvement initiatives to be processed with the involvement of the continual improvement practice or initiates a change request (if incident models, procedures, and automation are includedwithin the scope of the change enablement practice). |

| Incident modelupdate communication | If the incident model is successfully updated, it is communicated to therelevant stakeholders. This is usually done by the incident manager and/or the service or resource owner. |

4. Organizations and people

4.1 ROLES, COMPETENCIES, AND RESPONSIBILITIES

The ITIL practice guides do not describe the practice management roles such as practice owner, practice lead, or practice coach. They focus instead on the specialist roles that are specific to each practice. The structure and naming of each role may differ from organization to organization, so any roles defined in ITIL should not be treated as mandatory, or even recommended.

Remember, roles are not job titles. One person can take on multiple roles and one role can be assigned to multiple people.

Roles are described in the context of processes and activities. Each role is characterized with a competency profile based on the model shown in Table 4.1.

Table 4.1 Competency codes and profiles

| Competency code | Competency profile (activities and skills) |

|---|---|

| L | Leader Decision-making, delegating, overseeing other activities, providing incentives and motivation, and evaluating outcomes |

| А | Administrator Assigning and prioritizing tasks, record-keeping, ongoing reporting, and initiating basic improvements |

| C | Coordinator/communicator Coordinating multiple parties, maintaining communication between stakeholders, and running awareness campaigns |

| М | Methods and techniques expert Designing and implementing work techniques, documenting procedures, consulting on processes, work analysis, and continual improvement |

| Т | Technical expert Providing technical (IT) expertise and conducting expertise- based assignments |

4.1.1 Incident manager role

In many organizations, the incident manager role is performed by a dedicated person, sometimes under the incident manager job title. In other organizations, the responsibilities of an incident manager are taken by the person or team responsible for the CI, service, or product with which the incident is associated; this may be the resource owner, service owner, or product owner.

This role is typically responsible for:

- the coordination of incident handling in the organization or in a specific area, such as territory, product, and technology, depending on the organizational design

- coordinating manual work with incidents, especially those involving multiple teams

- monitoring and reviewing the work of teams that handle and resolve incidents

- ensuring sufficient awareness of the incidents and their status across the organization

- conducting regular incident reviews and initiating improvements of the incident management practice, the incident models, and the incident handling procedures

- developing the organization’s expertise in the processes and methods of the incident management practice.

In some cases, organizations may introduce the additional role of the major incident manager (MIM). This role has similar responsibilities to the incident manager but focuses exclusively on major incidents. This role becomes the main point of contact and coordination during major incidents. The MIM usually has wider authority and may have dedicated resources for major incident management.

The competency profile for these roles is LCTA, though the importance of each of these competencies varies from activity to activity.

4.1.2 Other roles involved in incident management activities

Examples of other roles which can be involved in incident management activities are listed in Table 4.2, together with the associated competency profiles and specific skills.

Table 4.2 Examples of roles with responsibility for incident management activities

| Activity | Responsible roles | Competency profile | Specific skills |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incident handling and resolution process | |||

| Incident detection | Technical specialist Users | TC | Understanding of the service design, resource configuration, and business impact of events and symptoms |

| Incident registration | Incident manager Service desk agentTechnical specialist | AT | Good knowledge of IT service management (ITSM) tools and procedures |

| Incident classification | Incident manager Service desk agent Technical specialist | TC | Understanding of the service design, resource configuration, and business impact Good knowledge of requirements and commitments for incident resolution Good knowledge of incident models |

| Incident diagnosis | Supplier Technical specialist | TC | Understanding of the service design, resource configuration, and business impact Knowledge of incident models, diagnostic tools, methods Analytical skills |

| Incident resolution | Supplier Technical specialist User | T | Understanding of methods and procedures required for incident resolution |

| Incident closure | Incident manager Service desk agent Technical specialist | ACT | Understanding of the service design, resource configuration, and business impact Good knowledge of the requirements and commitments for incident resolution |

| Periodic incident review process | |||

| Incident review and incident records analysis | Incident manager Product owner Service owner Supplier | TCL | Understanding of the service design, resource configuration, and business impact Good knowledge of the requirements and commitments for incident resolution Knowledge of incident models,diagnostic tools, methods, and analytical skills |

| Incident model improvement initiation | Incident manager Product owner Service owner | TMC | Understanding of the service design, resource configuration, and business impact Good knowledge of the requirements and commitments for incident resolution Knowledge of incident models, diagnostic tools, and methods Knowledge of the organization’s continual improvement and change enablement practices |

| Incident model update communication | Incident manager Product owner Service desk agent Service owner | CA | Knowledge of communication procedures and tools |

4.2 ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURES AND TEAMS

he incident management practice does not recommend any particular organizational model. However, the organizational structure influences how the practice is performed, as it involves specialists with different areas and levels of expertise. Typical methods of grouping specialists include, among others:

- technical domain

- product/service

- territory

- consumer types.

The method of organization will vary, depending on the organization’s needs and resources. The incident management practice should take a flexible approach to its organization, involving resources from various internal and external teams as necessary.

4.2.1 Tiered versus flat team structures

Historically, teams working on incidents had a tiered or levelled structure in which competency, expertise, and specialization increased with each level. It aimed to resolve most of the incidents at the lowest level possible to reduce costs. Incidents were transferred to the upper level, or escalated, if they could not be resolved in the current level. In such teams, there were clear boundaries between levels and clear procedures for the escalation of incidents. Unfortunately, such structures can restrain collaboration and information flow, resulting in prolonged resolution time. So, for high-priority incidents, teams collaborate to facilitate speedy resolution.

The expansion of Agile methods and quality changes in IT systems (such as self-healing systems) call for the wider use of horizontal team structures, rather than hierarchical team structures. Flatter structures and respective collaboration methods, such as swarming, replace tiered ones to facilitate cooperation and the free flow of information. The main driver of such change is the rejection of rigid tiering and its replacement by a more dynamic, self-organized collaboration.

Example

A typical escalation process within a three-tiered (L1, L2, L3) team could be replaced by the following:replacing L1 to L2 escalation with a flattened system of pairing (or similar) with the goal of faster resolution and flow of remaining issues to L3inter-team collaboration at L3 to replace multiple re-assignments and/or over- reliance on experts and champions.

4.2.2 Team dynamics

The incident management practice is the foundation of team dynamics, because they affect the functioning of the support operation. The following issues regularly recur:

- incidents are redirected between teams

- team members experience a lack of autonomy and report being blocked by others

- a culture prevails where lone ‘heroes’ are rewarded when incidents are solved.

This leads to the incident management practice being out of sync, resolutions happening slowly or not at all,

a decrease in morale, a lack of motivation, and an unhealthy degree of competitiveness entering the

workplace. Furthermore, trust between team members breaks down. Approaches such as DevOps and

swarming show some of the characteristics needed to encourage a positive culture, although it is not necessary to follow these approaches to achieve the correct team dynamic. The following three main areas need to be addressed.

4.2.2.1 Collective responsibility

If resolving incidents is the primary responsibility, that is what individuals within the teams will focus on. Team dynamics come second to achieving the SLA or meeting a deadline. The first step in changing this is to build a culture where team members share successes and failures. Teams that share responsibility may have a single person who sees an incident through to resolution, but they should be encouraged to engage other experienced people in the process. When this occurs, the organization will benefit from a fast restoration of normal service as well as knowledge- sharing.

4.2.2.2 No-blame culture

There should be a no-blame culture within teams; otherwise, this will lead to the deterioration of trust between individuals, teams, and suppliers. Incident investigations and reviews need to address incident resolution and service restoration. Incident teams must be encouraged to act without fear of retribution if their idea fails to work.

4.2.2.3 Continual learning

Team members need to share the lessons that they have learned from experimenting so they can learn and improve. This can prove to be a significant cultural leap in many environments, particularly those with a large percentage of outsourcing.

5. Information and technology

5.1 INFORMATION EXCHANGE

The effectiveness of the incident management practice is based on the quality of the information used. This includes, but is not limited to, information about:

- customers and users

- architecture and design of services

- partners and suppliers, including contract and SLA information on the services they provide

- policies and requirements which regulate service provision

- stakeholder satisfaction with the practice.

This information may take various forms, depending on the incident models in use. The key inputs and outputs of the practice are listed in section 3.

Details of incidents are the most important pieces of information. These usually include:

- sources of information

- a reference to the product, service, or CI that is failing or performing below standard

- the impacted users or services

- the symptoms of the poor performance

- when the symptoms are observed

- the last known time of correct operation before the symptoms began

- whether an automatic fix was applied (and if not, the reason)

- the location, both geographic and virtual

- the nature and extent of the impact on normal operations

- similar systems which might be affected by the poor performance and are currently operating normally

- the sequence of events leading up to the observation of the symptom.

Additional information that will be exchanged and recorded during the incident management practice should include details of:

- the investigation (if any)

- every action taken, including the results.

Any actions taken should be documented to produce an accurate timeline. If it is not practical to document actions in real time, the documentation should specify when the action was started and completed to avoid the creation of a false history log. It is preferable, however, to capture real- time actions if the customer can see the information through a portal. Where possible, the registration of actions should be automated.

Incident records should be presented so that they follow the natural workflow of the support agent or expert, and should include the data shown in Table 5.1.

Table 5.1 Data to be included in incident records

| Field | Recommended content | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Incident title (short description) | The function or process and the observed fault or degradation | The search for solutions is faster with a clear description |

| User | Affected user(s), reported user | |

| Current impact | Text explanation of actual effect on user/customer workflow | Creates context to allow the resolver group to offer appropriate workarounds or fixes |

| Future impact | Text explanation of potential impact on customers while the incident continues | Creates context to allow the resolver group to offer appropriate workarounds or fixes |

| Time of the first symptom | Date and time from either monitoring or user experience | Pinpoints the moment before which causal factors will be investigated |

| Time of last good function | Date and time when function is verified as normal | Pinpoints moment after which trigger event should be found (whether this information is added by person or logged automatically may affect credibility) |

| Detail of affected item (function, CI, process) | Asset ID numbers, application and process names, and CI reference | Focuses efforts for remediation |

| Detail of comparable item not affected (ifany) | Unaffected asset ID numbers, application and process names, and CI reference | Narrows the search for cause |

| Investigation detail (if relevant) | Steps taken to investigate and results of steps | Minimizes repeat work |

| Assigned to | Person or group that owns the incident | |

5.2 AUTOMATION AND TOOLING

The incident management practice should be automated. Where this is possible and effective, it may involve the solutions outlined in Table 5.2.

In some cases, all activities after a particular activity in the incident handling and resolution process can be fully automated using pre-defined scripts and scenarios for specific types of incidents.

Note that automation tools used in the incident management practice could include not only organization-wide tools, which are valid for all incidents, but also some local custom tools and scripts created as a result of a periodic incident review process for specific incident models. Both should be used to drive automation efforts.

Table 5.2 Automation solutions for incident management activities

| Process activity | Means of automation | Key functionality | Impact on the effectiveness of the practice |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incident handling and resolution process | |||

| Incident detection | Monitoring tools and event correlation engines | Early detection and correlation of incidents, initiating the incident management practice | High |

| Incident registration | User query management and workflow tools, and collaboration tools | Efficient registration of incidents | High |

| Incident classification | User query management and workflow tools, collaboration tools, knowledge management tools, configuration management tools, and machine-learning based classification engine | Fast and correct classification and assignment of the incidents, identification of known solutions, identification of major incidents | Very high, especially when the number of incidents is high |

| Incident diagnosis | Analysis and investigation tools, knowledge management tools, configuration management tools,and collaborationtools | Fast and correct definition and testing of hypothesis, effective collaboration of multiple specialists/teams | High, especially when the number of complex incidents requiring manual collaborative efforts is high |

| Incident resolution | Remote administration tools, automated deployment systems,and collaboration tools | Fast correction of the faulty CIs and restoration of the services | High, especially when services are provided in remote locations |

| Incident closure | User query and workflow management tools, and collaboration tools | Fast and comprehensive overview of the incident lifecycle | Medium |

| Periodic incident review process | |||

| Incident review and incident records analysis | Collaboration systems, analytical and reporting systems, and survey tools | Remote collaboration, incident data analysis, and users survey data analysis and reports | Medium to high, especially for high volumes of incidents |

| Incident model improvement initiation | Workflow systems and backlog tools | Formal registration of the initiatives | Low to medium |

| Incident model update communications | Communication systems and collaboration systems | Communicating updates to the affected teams | Medium to high, especially when organization is large, and number of updatesis high |

6. Partners and suppliers

Very few services are delivered using only an organization’s own resources. Most, if not all, depend on other services, often provided by third parties outside the organization (see section 2.4 of ITIL Foundation: ITIL 4 Edition for a model of a service relationship). Relationships and dependencies introduced by supporting services are described in the practice guides for service design, architecture management, and supplier management.

Incident models should define how third parties are involved in incident resolution and how the organization ensures effective collaboration. This will depend on the architecture and design solutions for products, services, and value streams. Nonetheless, the optimization of incident models supporting these solutions will involve the incident management practice. Generally, after the correct model is selected for an incident, further consideration of third-party dependencies is needed during incident diagnosis, resolution, and review.

Defined standard interfaces may become an easy way to communicate conditions and requirements in order for a supplier to become a part of the organization’s ecosystem. Such interface description may include rules of data exchange, tools, and processes that will create a common language in the multi-vendor environment.

Where organizations aim to ensure fast and effective incident resolution, they usually try to agree close cooperation with their partners and suppliers, removing formal bureaucratic barriers in communication, collaboration, and decision-making (see the supplier management practice guide for more information).

7. Important reminder

Most of the content of the practice guides should be taken as a suggestion of areas that an organization might consider when establishing and nurturing their own practices. The practice guides are catalogues of topics that organizations might think about, not a list of answers. When using the content of the practice guides, organizations should always follow the ITIL guiding principles:

- focus on value

- start where you are

- progress iteratively with feedback

- collaborate and promote visibility

- think and work holistically

- keep it simple and practical

- optimize and automate.

More information on the guiding principles and their application can be found in section 4.3 of ITIL Foundation: ITIL 4 Edition.